Spotting some errors in her own work she withdrew the paper but carried on with her microscopic studies for some years. Massee introduced the paper on her behalf because as a woman she was not permitted to attend proceedings or read her paper. Rejected by the then Director of Kew – as both a female and an amateur – she submitted her paper, On the Germination of the Spores of the Agaricineae, to the Linnean Society in 1897.

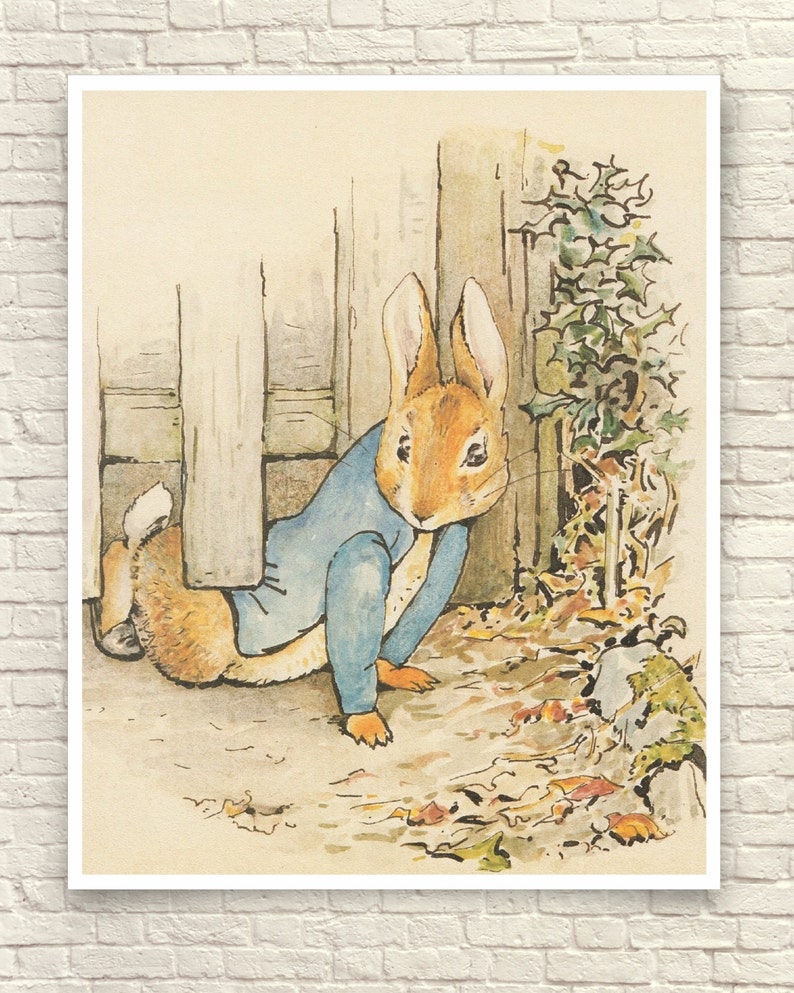

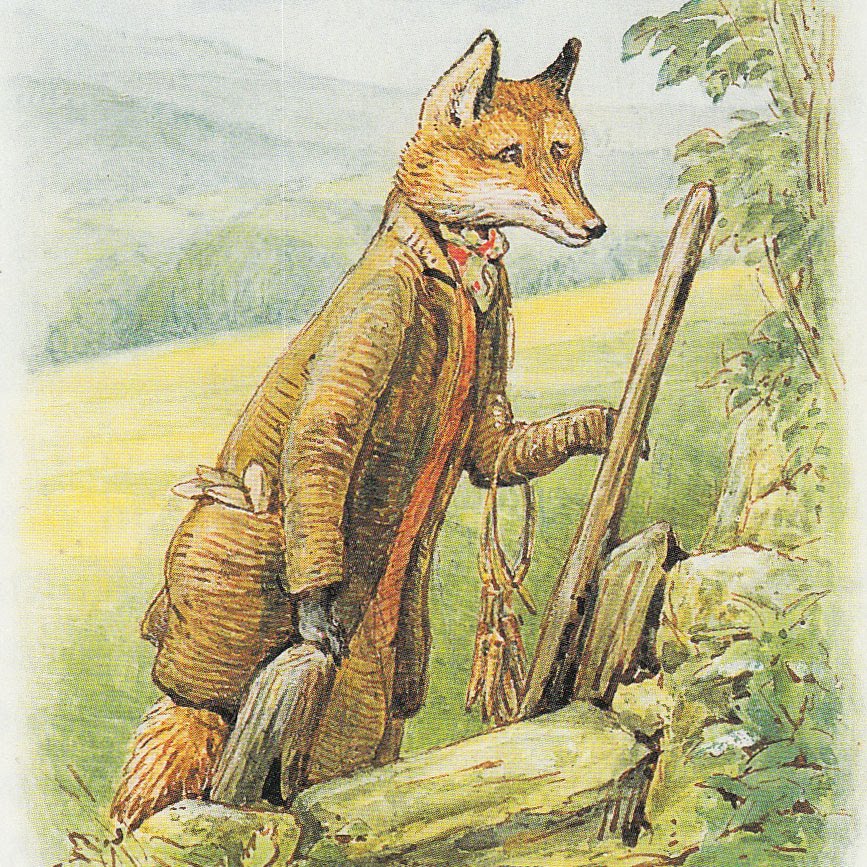

She corresponded with botanists at Kew, and convinced George Massee (first President of the British Mycological Society) of her ability to germinate spores and her theory of hybridisation. Curious as to how they reproduced, she began microscopic drawings of fungus spores and developed her own theory of their germination. She painted the animals, plants and fungi she saw there and although her parents discouraged any academic – especially scientific – aspirations, they encouraged her painting, a suitable occupation for a Victorian young lady.įirst drawn to fungi through painting them and capturing their delicate colours, she gained more scientific knowledge from respected amateur mycologist Charles McIntosh, who taught her taxonomy, and supplied her with live specimens. She loved the countryside of Scotland and the Lake District where she, her brother and their parents spent holidays. She was an outstanding artist, a noted conservationist… and a significant scientist in the field of mycology (the study of fungi).īorn into a privileged household in July 1866, the young Beatrix was educated by governesses and mixed little with other children. 2016 marks 150 years since the birth of a woman whose books have delighted generations of children (and their parents)īut there is far more to Beatrix Potter than Peter Rabbit, Jemima Puddleduck and Squirrel Nutkin.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)